Musical Notes - Everything You Need To Know

Read Time: 7 Minutes

Note Names & How To Read Them

We write musical notes on a staff (known as a ‘stave’ in the UK). Each line or space on the staff represents a different note, and this is how we read the music note names.

There are two main types of staff we use:

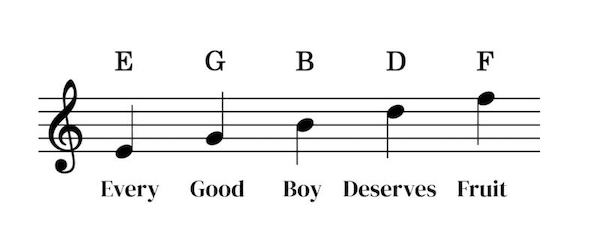

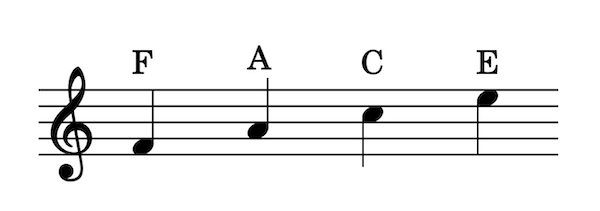

The Treble Clef

The swirl in the middle of this clef points to the line for the note G above middle C (C4 on the keyboard). This clef is used for the right hand on the piano or high-pitched instruments like the flute.

We can use mnemonics to help remember the order of the notes, like so:

For the lines: Every Good Boy Deserves Fruit

And for the spaces, the word F A C E.

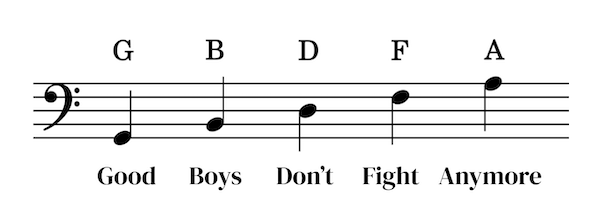

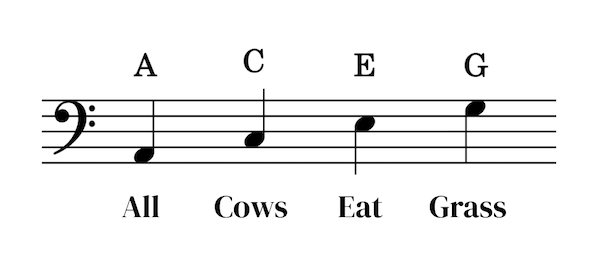

The Bass Clef

The swirl on this clef points to F below middle C. This clef is used for the left hand on the piano or lower-pitched instruments like the cello.

Some mnemonics to help remember this clef:

For the lines: Good Boys Don’t Fight Anymore

And for the spaces: All Cows Eat Grass

Types of Notes - Beats & Length

While the position on the staff tells us the pitch of musical notes, their shape will tell us their ‘value’, or how long the note is. There are 6 main types of music notes. We’ll use the American names for the notes, with the British name in brackets.

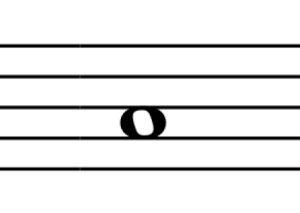

Whole Note (Semibreve)

This note lasts for 4 beats. A lot of music has 4 beats per bar, so this note would last for one whole bar. The oval shape is called the ‘head’.

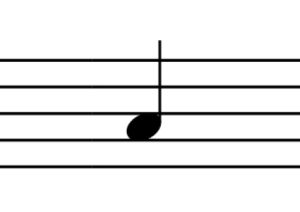

Half Note (Minim)

This note is half the value – it lasts for 2 beats. Notice it has grown a stem from its head. The stem should point upwards on the right side if the note is below the middle line (B in treble clef), or downwards on the left side if the note is above the middle line. If it’s in the middle, either can be used.

Quarter Note (Crotchet)

Halved again, this note lasts for one beat. It still has a stem and is now colored in.

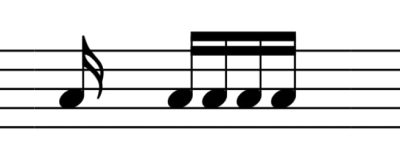

Eighth Note (Quaver)

You guessed it – this note lasts for half a beat, so two of them together would take up one beat. The stem has the addition of a tail on the end.

When we have multiple eighth notes next to each other, we can join them together with a beam. We use beams to make these smaller notes easier to read and to make it clearer where the beat is. All notes with tails can be beamed together, no matter their type.

Sixteenth Note (Semiquaver)

This note lasts for a quarter of a beat, so four of them would take up one beat. The stem now has a second tail on it, and we’ll use two beams.

32nd note (Demisemiquaver)

Don’t worry, you likely won’t need any smaller types of notes than these. This lasts for an eighth of a beat, so eight of them would take up one beat. The stem has 3 tails, and we’ll use 3 beams.

Types of Notes - Accidentals

Musical notes can have their pitch modified by an ‘accidental’.

If we write out all notes without an accidental, we get the C major scale or all the white keys on the piano.

To use other notes (like the black keys) we need to add accidentals.

Let’s run through different types of accidental and how they the affect the pitch of different notes.

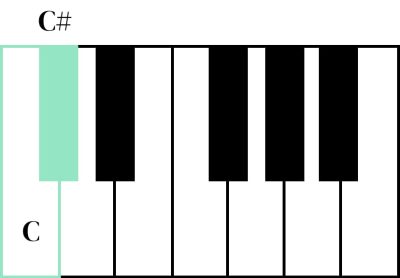

Sharp

The sharp symbol moves a note up one half step, also called a semitone in British English. This is one note upwards on the piano keyboard.

You can remember it by the fact a shaRp moves a note to the Right on the keyboard.

For example, C with a sharp becomes C♯.

In musical notation these notes would be represented as:

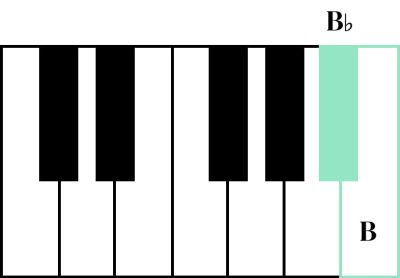

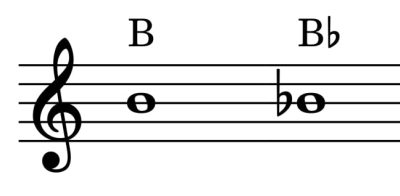

Flat

The flat symbol moves a note down one half step (or one semitone).

You can remember it as a fLat moves to the Left on the keyboard.

For example, B becomes B♭.

On the piano these would be the following notes:

Which in musical notation are represented as:

Key Signatures & Notes

You will see sharps or flats added at the front of the staff on every new line of notation. This is called the ‘key signature’. The key signature tells us that all music notes on that line/space will be either be sharp or flat, according to the symbol used.

For example D Major, which has two sharps (F# and C#) is written as the below.

We can also use notes outside of the key signature by adding a sharp or flat just before them. For example, the key of C has no sharps or flats. However we can add a G# and Bb using accidentals, as below.

Natural

What if our key signature tells us to use F♯, but we just want to use a normal F? This is where the natural sign comes into play.

The natural sign cancels out any sharp or flat, so F♯ moves down a half step and becomes F♮.

Double Sharp

We can also double up accidentals. Two sharps together make a double sharp, which means the note moves up two half steps (or a tone).

There isn’t a way to type the double sharp, so we usually use ‘x’ or ‘♯♯’ instead.

An example would be, if we applied a double sharp to G, this would become G♯♯, which makes it the same pitch as A (by moving up two half steps).

Double Flat

A double flat moves a note down two half steps (or a tone).

For example, B♭♭ is also equivalent to A.

The reason we use double sharps and flats gets a bit complicated, but it mainly has to do with scales.

For example, the harmonic minor scale has a sharpened 7th note. If that note was already a sharp note such as F♯, we would need to sharpen it AGAIN to make the scale.

In Summary

To summarize this all, there are three different pieces of information we can learn about musical notes by looking at them in notation.

- The pitch. We can tell the pitch of the note by which line or space it occupies on the staff. This could be a treble clef staff for higher-pitched instruments or a bass clef staff for lower ones.

- The value (length). We can tell how many beats a note lasts by its shape. Whether the head is colored in, whether it has a stem, whether it has tails, how many tails it has…

- Whether the pitch is altered. The position on the staff tells us the pitch, but this can be altered by symbols like flats or sharps. Sharps move up a half step, flats move down a half step.